by Laura Jones

Updated on April 7, 2025

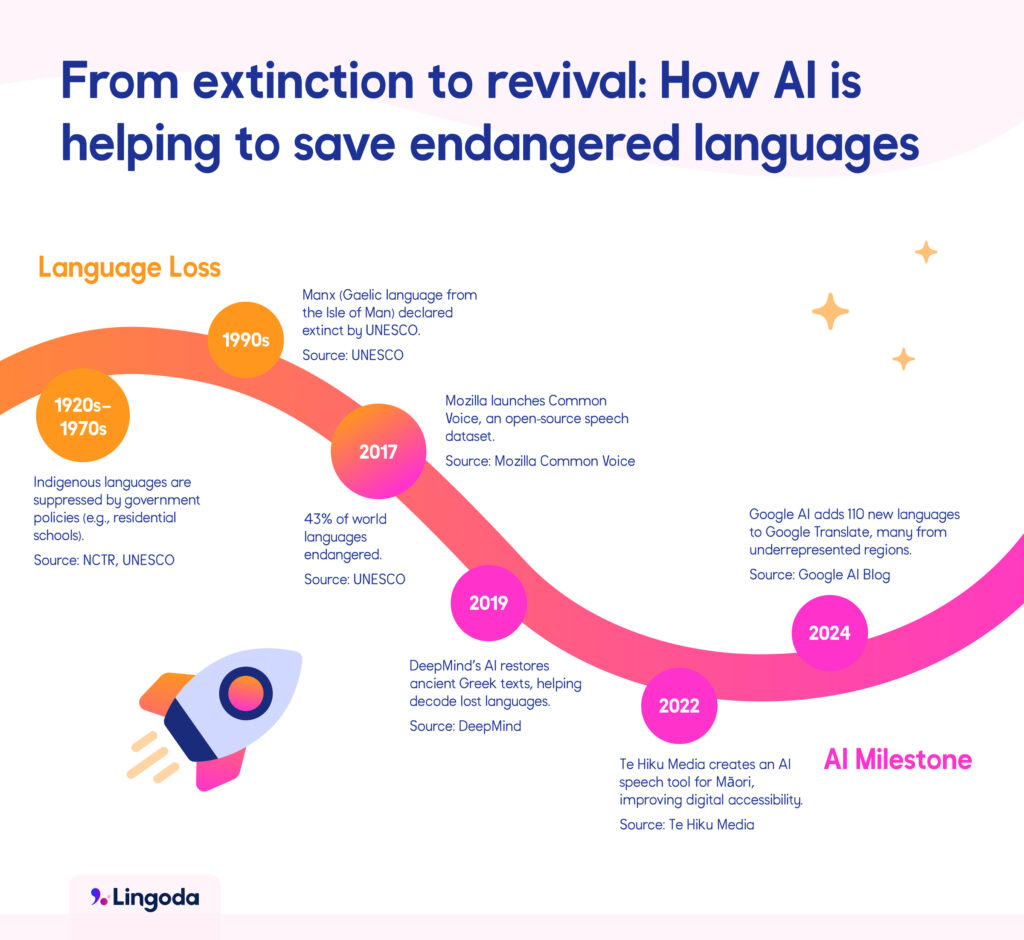

Of the thousands of languages spoken in the world today, UNESCO estimates that around 43% are endangered. AI is stepping up to bring them back from the brink. It can be used to create a digital archive of endangered languages, leveraging tools like speech-to-text and its ability to process enormous amounts of data. However, ethical concerns around their preservation exist. So, how exactly is AI helping to save endangered languages?

UNESCO classifies the degree of endangerment of languages on a scale of “safe” to “extinct”. In between are “vulnerable”, “definitely endangered”, “severely endangered” and “critically endangered”.

Why are so many languages in danger of disappearing, and what happens when they do? According to the Harvard International Review, external pressures play a key role. Dominant languages like English, Spanish and Mandarin Chinese marginalize Indigenous languages. This is because people often see proficiency in these dominant languages as the gateway to better jobs or education. Urbanization and industrialization accelerate this trend, along with media, which publishers often distribute in major world languages.

Government policies can also have an impact. An example is the Canadian government’s forced removal of Indigenous children from their families to attend residential schools between 1831 and 1996. It meant parents couldn’t speak their language to their children. When languages disappear, communities lose unique cultural identities, traditional knowledge, and worldviews embedded in them. In return, people lose connection to their culture and history, which can result in them losing their identity and sense of self.

While globalization and technology have often been blamed for the loss of languages in the past, AI has now become a possible preservation tool. Text-to-speech tools can convert spoken language into written text, helping to preserve oral languages without the need for manual transcription. Automated translations can make lesser-spoken languages more accessible, and AI-driven data collection is much faster than manual language documentation.

AI has already achieved success. New Zealand’s Te Hiku Media created an automatic speech recognition tool that can transcribe speech-to-text with 92% accuracy for Te Reo Māori. Similarly, the app Tarjimly, billed as an “Uber for Translators”, records real conversations between translators and refugees for AI training.

AI has become instrumental in identifying, transcribing, and synthesizing speech in rare and endangered languages. Projects like Mozilla’s Common Voice collect diverse speech samples to enhance AI models’ understanding of these languages. Mozilla launched Common Voice in 2017 as an open-source initiative. Contributors have recorded thousands of hours of speech in 133 languages, helping Common Voice create one of the most extensive free AI voice datasets.

AI-driven voice synthesis also plays a crucial role in reconstructing and teaching lost phonetics. By analyzing existing audio recordings, AI can generate accurate pronunciations of words and phrases. This helps in the preservation and education of endangered languages.

AI can help bridge the communication gaps between endangered and dominant languages through machine translation and NLP. Google, for instance, expanded its translation services to include lesser-known languages by training AI models on limited datasets. In 2024 alone, AI helped expand Google’s translation services to 110 new languages, about a quarter of which are from Africa.

However, certain languages lack training data, which makes AI models less accurate. Collaborative efforts are underway to address this. For example, the Government of Nunavut partnered with technology firms to develop AI models that support the Inuktitut language, making the language more accessible.

AI-driven chatbots and virtual tutors offer interactive platforms for learners to practice endangered languages. These tools simulate conversations, provide real-time feedback, and create engaging learning experiences for new generations of learners. For instance, KumuBot is an all-in-one chatbot, translator and gamified teacher of the Hawaiian language, which was nearing extinction in the 1980s.

AI can also be used to generate custom learning materials in languages with few teaching resources, while AI-powered chatbots can offer immediate pronunciation feedback. Certain apps also leverage the power of AI to create personalized learning pathways.

Finally, AI-driven research can help us decipher long-lost languages, even if only fragments of the language exist. An example is Google’s DeepMind, created text restoration models to reconstruct missing characters in incomplete ancient Greek texts. By processing vast amounts of linguistic data, AI can uncover grammatical and phonetic patterns and relationships to known languages that might take humans months or years to discover. Plus, AI is achieving a 30.1% character error rate compared to 57.3% for human experts.

Researchers are also using AI to translate vast amounts of materials from ancient languages quickly. For example, AI has recently been used to translate cuneiform tablets from Akkadian (the language of ancient Mesopotamia) into English, allowing us to recover a wealth of knowledge about society and culture.

One major challenge AI faces is the bias in training data, as most AI models are trained primarily on dominant languages. The small datasets we have for many indigenous languages mean AI tools are trained less efficiently. Take one Reddit user’s post about Manx, a language UNESCO declared extinct in the 1990s but that has seen a revival. The user states simply that Google Translate’s AI-powered tool is “beyond awful at translating words.”

An additional concern is the risk of AI replacing native speakers as a method of language transmission. AI should be a means of fostering greater communication between human beings, not replacing it. If you engage with a language via AI only, the rich context and cultural nuances that human beings can provide are lost.

Data ownership is also a pressing issue, which broadly concerns most internet users, no matter the language they use to communicate. Zoom users, for example, were outraged when the platform changed its terms of service to allow it to use conversations to train its model. For indigenous communities, control over their linguistic heritage is a must.

Is the future bright for endangered languages? There are signs that it might be. Collaboration between communities and AI researchers will be key and is already happening. For example, the Icelandic government is getting ahead of its language’s possible extinction by working with OpenAI to broaden the use of Icelandic and other marginalized languages.

Public policies can also play a crucial role in supporting AI-driven language preservation initiatives. Governments can implement strategies that encourage AI research focused on endangered languages. For example, the UK’s AI Opportunities Action Plan emphasizes investment in AI infrastructure and cross-sector adoption. The responsibility also lies with tech companies, which can themselves fund community-led AI projects. Cooperation between AI researchers, governments, and native speakers is the path forward to ensure AI is a friend, not a foe, in the fight to preserve linguistic diversity for future generations.