by Laura Jones

Updated on January 8, 2024

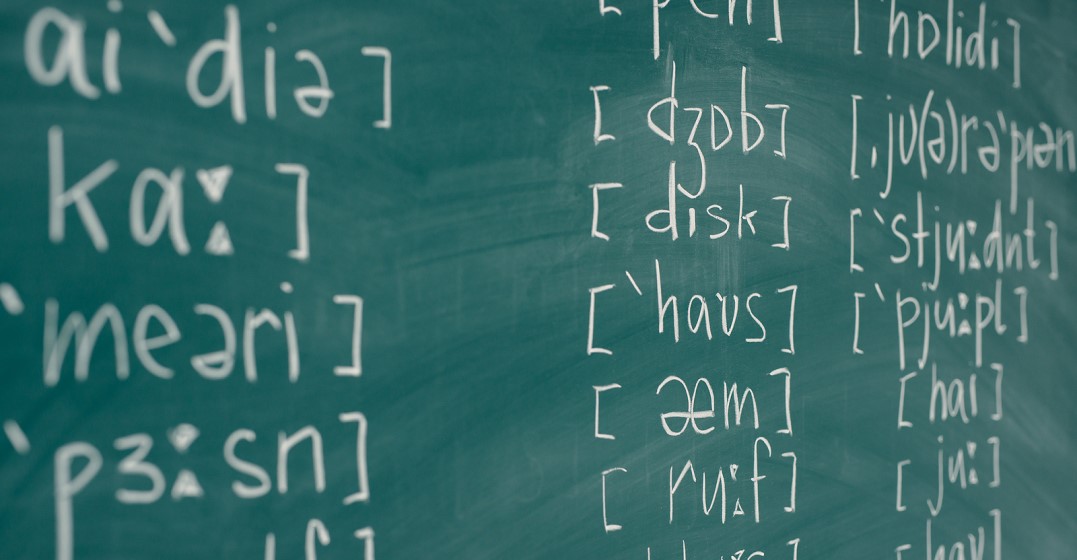

Kæn juː riːd ði aɪ-piː-eɪ?

Reading that question you might think you’ve stumbled across a blog written in Klingon. Fear not, earthlings. The sentence above is in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), and by the end of the lesson you’ll not only know how to read it, but you’ll actually want to use it in your language learning as well. Phonetic language learning is fun, read on!

The IPA is a written way to show how words are pronounced. If you know it, you can read a word in any language and know how to pronounce it. How amazing is that?!

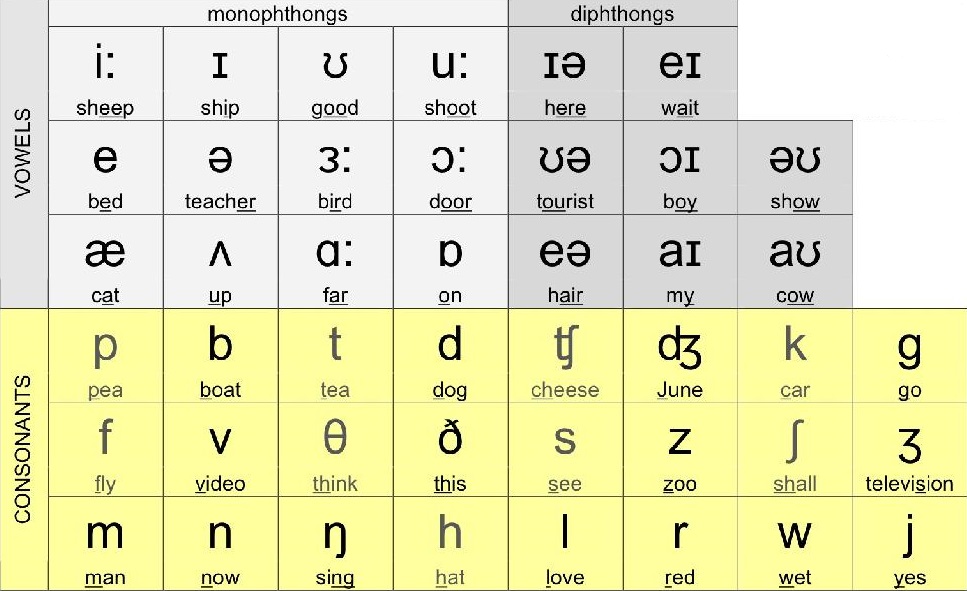

We are going to concentrate on the English sounds to learn the phonetic alphabet in particular in this blog. Here they are:

Can you read the sentence at the beginning by using the chart?

You might think that you don’t need to read pronunciation symbols anymore because you can just get Google translate to say the word to you. Well… if you’ve ever heard the Google guy or gal saying a word in your own language, you’ll know it can be a bit robotic at best, and just plain wrong at worst. So being able to read how something should be pronounced is still really helpful.

With some languages, you can look at a written word and know how to pronounce it. These languages are phonetic, and include Polish and Finnish (yes, those super useful, widely-spoken languages). However, you might have already discovered that English isn’t a phonetic language. This makes it really hard to know how to pronounce a word that you have only seen written down. Take the example of the word read; it can be pronounced /riːd/ or /rɛd/ depending on context. In addition, the same sound can be created with different letters. For example, he, believe, machine and sea all have the same /iː/ sound with different letters. Similarly, the same letter can make different sounds; thing /θ/ and the/ð/, for example. In any case, the IPA is really useful and saves you from pronouncing even simple words like parent /ˈpeərənt/ and mountain /ˈmaʊntɪn/ incorrectly. (Is it only my students who insist on saying parrent and mountayn?)

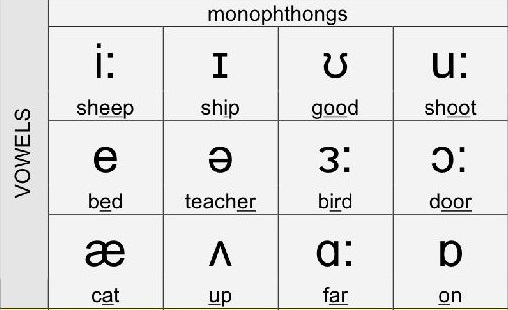

An incredible thing about the IPA for English is that it shows you how to move your mouth to pronounce the sounds. The layout of the chart tells you how your mouth, tongue and jaw should be positioned. Look at the monophthongs (vowels with one sound) here. Now imagine a person walking up to this chart from the right and trying to swallow it. It would get stuck, sure, but you would see exactly how to pronounce the sounds.

The /i:/ sound comes from the front and the top of your mouth, with an only slightly open jaw. The /ɒ/ sound comes from the back and the bottom of your mouth with a much longer, more open jaw. You will also notice that if you move along from left to right, for example from /i:/ to /u:/, your smile will get smaller and you’ll almost make kissing lips on the last letter.

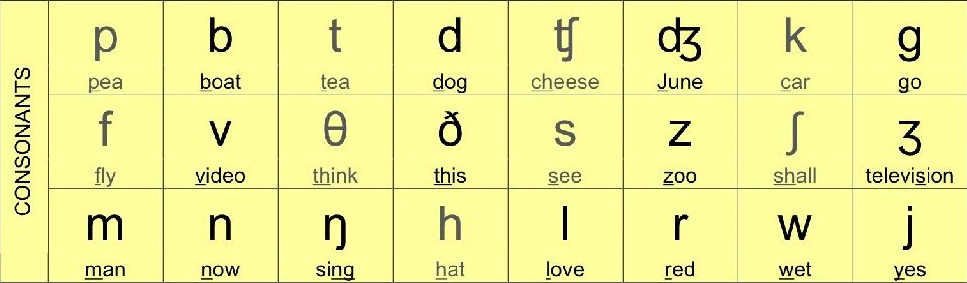

The consonants are arranged in a similar way on the phonemic chart. From /p/ at the front of your mouth to /g/ at the back. The top row are the stop sounds – sounds you make by stopping and then releasing them. The middle row are the friction sounds – the sounds that you can make longer, like /s/: ssssss. The bottom row are an assortment of sounds – English, once again, won’t conform completely.

Seeing a word or phrase written phonetically also tells you which syllables to stress. The stressed syllable is represented by an apostrophe – ‘ – before it. This is really helpful in general, but even more so when words and nouns are spelt the same but stressed differently. Take the word record. As a noun it is pronounced /ˈrɛkɔːd/ with the stress on the first syllable, and as a verb /rɪ’kɔːd/, with the stress on the second syllable.

The IPA can also be used to show how different accents are pronounced. Fancy yourself as a bit of a cockney geezer? It might help you to know that think is pronounced /fɪŋk/ rather than the regular /θɪŋk/. If you’re anything like my students, you might find the cockney way a lot easier.

If you want to sound like someone from the North of England, knowing that a lot of words contain a glottal stop is useful. This non-sound is transcribed as /ʔ/. It can be seen in words like bottle, where the t is missed and replaced by a so-called gasp of air: /bɒʔl/.

ði aɪ-piː-eɪ ɪz ˈrɪəli ˈjuːsfʊl.

ˈɪŋglɪʃ ɪz nɒt ə fəʊˈnɛtɪk ˈlæŋgwɪʤ.

ðæts ði ɛnd ɒv ðə blɒg!

The IPA can stop you from mixing up your /dɪˈzɜːt/ with the /ˈdɛzət/ – a difference of eating chocolate cake rather than sand after dinner. And that alone makes learning to read the phonetic alphabet really important.