The hardest German words to pronounce (and how to tackle them)

But what makes them so tricky?

Aside from their sheer length, which owes to the German tendency to combine multiple words into one longer word, these words rely on an impressive inventory of sounds. German includes several phonemes — like “ü,” “ö,” and that harsh “ch” — that don’t exist in English. Add in unpredictable rhythms and stress patterns, and suddenly your tongue is working overtime.

It can be a lot to handle. But, with the right strategies and some consistent practice, you’ll go from stumbling to smooth in no time. Let’s break down the toughest words and how to actually pronounce them.

10 difficult German words and why they are so hard

1. Eichhörnchen (squirrel)

The vowel-vowel-consonant mashup in the middle of this word is enough to trip anybody up. English speakers especially struggle to make the “ch” and “rn” flow together. Let’s break it down:

eye-ch-hoern-shen

Start with “Eich” [eye-ch] and get that sharp “ch” in your throat — not your mouth. Then “hörn” (say it like “hern” with a tight “ö” sound), and finally “chen,” which is a soft, breathy “shen.” Practice it slowly, piece by piece.

2. Streichholzschächtelchen (little matchbox)

It’s long. It’s a compound noun. It’s a tongue twister straight out of language nerd heaven.

shtrye-kh-holts-shekh-tel-khen

This one combines Streichholz (match) and Schächtelchen (little box). The trick? Chunk it. Don’t rush it.. And don’t worry if you can’t get it right, because it’s definitely not one of the most spoken words in German. It is good training for your throat sounds, though.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

3. Berühren (to touch)

That umlauted “ü” combined with a soft “r” in the middle makes the rhythm get weird.

buh-rue-ren

Focus on getting the “ü” right — it’s like saying “ee” while rounding your lips like you’re saying “oo.” And make that “r” gentle rather than rolled, almost like a soft tap.

4. Schluchztest (you sobbed)

It looks like a dare. All those consonants crammed together, and a “zt” at the end to top it up.

shlookh-ts-test

Start with “schluchzen” (to sob), which is already gnarly, then add “-test” for the second-person past tense. Go slow. Isolate each part. Breathe. Don’t sob.

5. Lehrerin (female teacher)

The rapid-fire repetition of the “r” sound throws off the flow, and the feminine “-in” ending doesn’t land cleanly for English speakers.

lair-uh-rin

Don’t panic on the double “r.” Instead, stretch it a bit. Start with “Lehr” (like the English “lair”) and then roll gently into “erin.” Say it almost like it’s two small words.

6. Nudeln (noodles)

That “-ln” ending can be tough, as English doesn’t really have an equivalent.

noo-duhln

Say “Nude-” like in “noodle,” then just tap the “l” and finish with an “n.” Super quick. Let it blur a little — it’s not supposed to be crisp.

7. Reparieren (to repair)

It’s long and repetitive, and those rolling “r” sounds are tough if you’re not used to them.

reh-pah-ree-ren

Make it musical. Stress the third syllable — which sounds like “ree” — and smooth out the rest. If your r’s aren’t rolling, keep them soft. Germans will still understand you.

What our students of German say

8. Großbritannien (Great Britain)

It’s a borrowed word, but German phonetics twist it into something new. Sounds familiar, until it doesn’t.

grohs-bree-tahn-yen

Don’t try to pronounce it like the English version. The German “ß” sounds like “ss,” and “Britannien” is three syllables. Emphasize the middle one, and keep the rhythm steady.

9. Eidechse (lizard)

That “ei” vowel blend, followed by a hard “ch” and “se” ending. Lots of little changes in your mouth position.

eye-dek-suh

Say “Ei” like “eye,” then “dech” (like “deck” but with a German “ch” in your throat), and finish with a soft “suh.” Think: smooth and light.

10. Rührei (scrambled eggs)

Umlaut + back-to-back vowels = chaos.

roo-er-eye

Start with the “Rüh” ([roo] with lips rounded), then ease into “ei.” It’s two syllables, but they blend. Don’t pause between them — just glide.

Tips to master these tough words

- Slow repetition and recording yourself: Say each word slowly and clearly, then listen back to hear what needs adjusting.

- Break words into syllables: Long words are less scary when you chop them into manageable parts.

- Shadow native speakers: Watch videos or join a class, and mimic what you hear — timing, tone and all.

- Practice full phrases: Phrases like “Welche Sprachen sprichst du?” help you get used to German rhythm, sibilants and flow.

The more you train your ear and mouth together, the more natural it all becomes. If you need some media support, this Youtube channel might be of some help, too!

What is the hardest word to learn in German?

This is subjective, but the prize may well go to Eichhörnchen, thanks to its tough sounds and lack of an English equivalent.

What is the longest, hardest German word?

We could award this one to the long, twisted compound word Streichholzschächtelchen.

However, the longest officially used German word is Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz, with an incredible 63 letters. This jumble of letters refers to “the law concerning the delegation of duties for the supervision of cattle marking and the labelling of beef.”

What is the hardest word to say in German?

It depends on what you struggle with, but schluchztest is a strong candidate due to its consonant overload, which makes it barely pronounceable for many a non-native German speaker.

Why pronunciation practice pays off

Mastering German pronunciation isn’t about perfection — it’s about confidence. Words like Eichhörnchen and Streichholzschächtelchen might trip you up now, but the more you practice, the easier it gets.

If you’re wondering how to learn German fast, Lingoda’s classes are designed to get you talking from Day One. We teach real-life, everyday German with a focus on pronunciation.. Stick with it, speak often and don’t be afraid to sound a little awkward — it’s all part of learning!

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

German capitalization rules: What to capitalize and why

The rules that govern German capitalization might seem daunting at first. Why is der Tisch capitalized while laufen is not? And what’s the deal with Sie vs. sie? Don’t worry — German is above all a systematic language, and once you understand the logic behind this system, reading and writing will become much easier.

In this guide, we’ll break down the essentials: which words are capitalized, which aren’t, and how to spot the common traps that trip up learners. We’ll also share some real examples and tips to help make it all stick.

- Why is capitalization important in German?

- Which words are capitalized in German?

- What’s not capitalized in German?

- Formal German, polite forms and exceptions

- Real-life examples and tips

- FAQs

Why is capitalization important in German?

German vs. English: A key difference in writing

If you’ve ever read a sentence in German and wondered why every other word seems to start with a capital letter, you’re not alone. Here’s the deal: German nouns are always capitalized. This rule applies not only to proper names, like Berlin or Angela Merkel, but also to common nouns ranging from Apfel (apple) to Zeitverschwendung (waste of time).

English uses capitalization much more sparingly, reserving it mainly for proper nouns and the beginnings of sentences.

What capital letters communicate in German

Interestingly, online learners — especially on community forums like Reddit — tend to agree that all those capitals are actually a helpful feature. Capitalization can make it easier to scan for meaning, especially in a language in which adjectives latch on to nouns, (making them potentially very, very long).

Because German nouns are capitalized, you can spot them at a glance. Think of them as little linguistic landmarks in a sentence. In this light, capital letters aren’t merely a formality — they’re a navigation tool.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Which words are capitalized in German?

All nouns, always

In German, every noun is capitalized — with no exceptions. If a word corresponds to a person, place, thing or idea, it starts with a capital. That includes animals (der Hund), emotions (die Freude), objects (das Buch), professions (der Lehrer) and even times of day (der Morgen). If it’s a noun, it’s capitalized.

Proper nouns and names

If all nouns are capitalized in German, it stands to reason that names of people, cities, countries and companies are capitalized — just like in English. You’ll see Anna, Berlin, Deutschland and Volkswagen all starting with a capital letter.

The first word in a sentence or quote

The first word of any sentence is always capitalized, even if it’s not a noun. The same goes for the first word in a direct quote. So, whether it’s “Guten Morgen!” or “Ich bin müde.”, the first word gets capitalized. This is true regardless of which part of speech it is.

What’s not capitalized in German?

Here’s where German flips the script from English. In German titles and headlines, verbs, adjectives and adverbs remain lowercase unless they’re the first word in a sentence. So, while an English headline might read, “Running Fast Is Fun,” the equivalent headline in German would state, “Laufen schnell macht Spaß.” Only “Spaß” is capitalized, because it’s a noun.

Many newcomers to German instinctively capitalize verbs when writing headlines or titles. This feels natural if you’re used to English, but it’s not how it works in German. If it’s not a noun and if it doesn’t start the sentence, it stays lowercase. No exceptions, no drama.

What our students of German say

Formal German, polite forms and exceptions

When adjectives or verbs become nouns (nominalization)

This is one of the trickier rules — but also one of the most common. When a verb or adjective is used like a noun, it gets capitalized. This is called Nominalisierung (nominalization). You’ll spot these nouns easier by looking for signal words that appear in front of them, such as articles (das, ein) and certain prepositions (zum, beim).

For example, consider das Lesen (reading) or beim Spazierengehen (while taking a walk). The nominalized word may look like a verb, but it’s acting like a noun, so it gets a capital letter.

Sie (formal ‘you’), Ihr (formal ‘your’), informal du and dein

What about “Ihr” or “Sie” in German? These words were in fact once capitalized in the formal correspondence of yesteryear. Today, the standard is to leave them lowercase, e.g., sie, ihr, du and dein.

Some people still capitalize these addresses in very formal and traditional writing, but it’s optional and fading fast. You’re safe sticking with lowercase, though it’s something to look out for if you spend a lot of time reading old German texts.

Real-life examples and practice tips

A good way to get the hang of German capitalization is to read short texts and spot the nouns. For example:

Heute Morgen hat der Lehrer dem kleinen Hund einen Ball gegeben.

How many capitalized nouns can you find? (Hint: Heute in this case is actually an adverb, not a noun. It’s only capitalized because it comes at the beginning of the sentence.)

This kind of practice trains your brain to recognize patterns, and it can help your writing feel more natural over time. At Lingoda, we build these kinds of real-world examples into our lessons, so you’re not just learning the rules — you’re using them.

Are pronouns capitalized in German?

Pronouns are not capitalized in German, except for the formal addresses Sie and Ihr (where it’s optional but common).

Are days of the week capitalized in German?

Yes, German days of the week (Montag, Dienstag, etc.) are capitalized because they are nouns, and all nouns in German are capitalized.

German capitalization rules in action: What to remember

German capitalization has its own logic, but once you get the hang of it, it starts to make perfect sense. Watch out for those noun-like verbs and formal pronouns, and you’re well on your way.

The best way to make it stick? Practice in real-life conversations. With Lingoda, you’ll speak from Day One, building confidence with help from native-level teachers who challenge you to apply the rules you learn in everyday situations. Enroll in one of our courses and you can learn German starting today!

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Mastering the past perfect tense in English

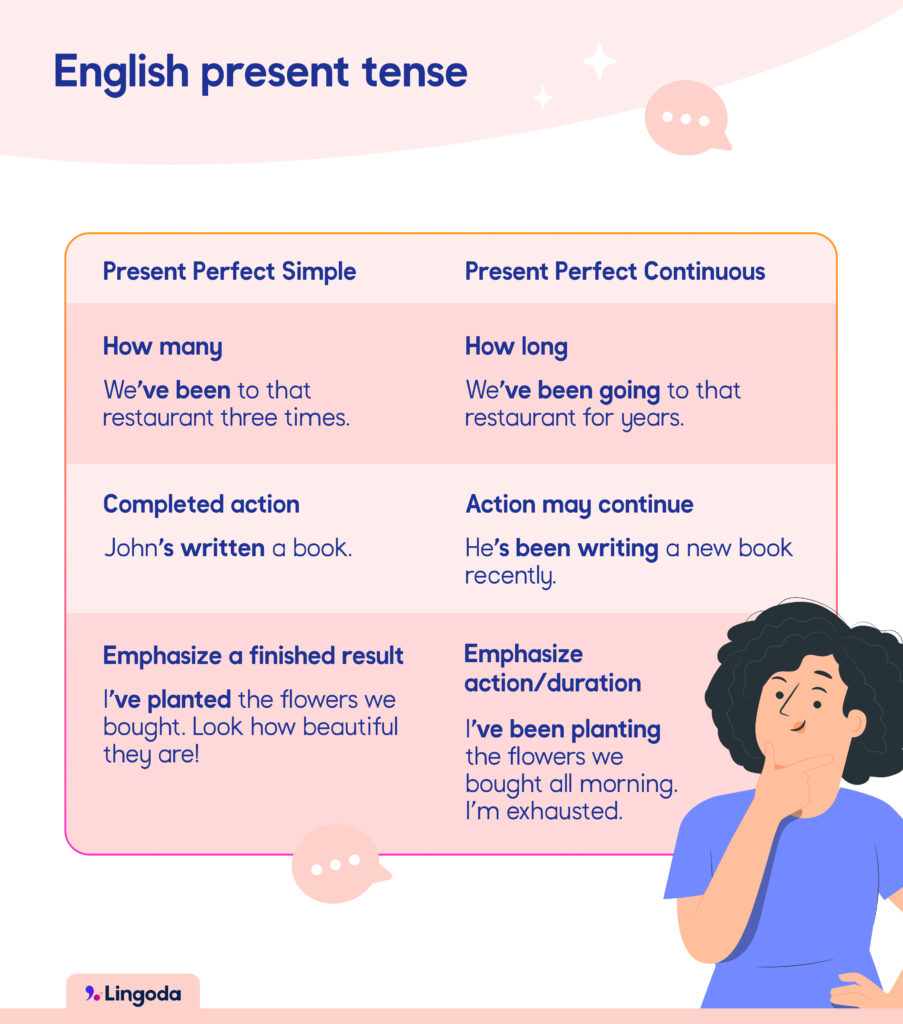

We use the past perfect tense to show that one action in the past happened before another. It clarifies the order of two past events or highlights the duration of a past event up to a specific time in the past. It helps you to tell stories, which is a huge part of our day-to-day communication.

While it’s considered one of the more advanced English tenses, using the past perfect tense accurately in exams can give you an edge. It can also make your speech and writing appear more professional, and it’s key in academic writing.

In this article, we’re looking at how to form the past perfect tense, which adverbs it often appears with, how and when to use it, and, crucially, when to avoid it.

- What is the past perfect tense?

- How to form the past perfect tense

- How to make the past perfect negative

- How to ask questions in the past perfect tense

- Examples of past perfect in context

- When NOT to use the past perfect tense

- The role of “just” and other modifiers

- Common mistakes learners make with the past perfect

- FAQs

What is the past perfect tense?

The past perfect simple tense is one of the 12 English tenses, and one of the four used to talk about the past..It’s used to show the sequence of two past events, with the past perfect marking the earlier one. It applies to both states and actions, including those that happen repeatedly. You can also use the past perfect to talk about how long something lasted up to a particular moment in the past.

It’s often called a “narrative tense” because of how useful it is for storytelling. It helps set a timeline and clearly indicates when things happened in relation to one another.

Learn English with Lingoda

How it works

How to form the past perfect tense

The formula

The structure of the past perfect simple tense is had + past participle, or more fully, subject + had + past participle verb form. We use had with all subjects, for example:

- I had

- You had

- She had

- They had

Common regular & irregular verbs

Remember that regular past participles are formed by adding -ed to a verb in the base form.

- ask → asked

- call → called

- start → started

These verb endings can be pronounced in three different ways.

- /ɪd/ after t or d sounds (forming an extra syllable)

→ started, wanted, needed

- /t/ after unvoiced sounds like k, p, s, sh, ch, th, f

→ asked, helped, passed

- /d/ after voiced sounds (everything else except t/d)

→ called, played, opened

Example sentences

- I had asked him before.

- We had called him earlier.

There are also many irregular verbs in English. Here are some of the most common ones with their past participle form:

- be → been

- come → come

- go → gone/been

- have → had

- know → known

- speak → spoken

- understand → understood

Example sentences

- They had been together for 50 years by 2020.

- I had spoken to him before.

What our students of English say

How to make the past perfect negative

To form a negative sentence in the past perfect simple, we use the structure had not + past participle. We often contract had not to hadn’t in informal speech and writing.

Example sentences

- I had not opened the present.

- They hadn’t been to Greece before.

How to ask questions in the past perfect tense

To form questions in the past perfect simple, we invert the subject and had. For yes/no questions, the structure is Had + subject + past participle?

- Had you met before?

To form wh-questions in the past perfect simple, we place the question word before had.

- What had he done?

- Where had she been?

Examples of past perfect in context

At a job interview

I’d already done internships at three different companies by the time I finished university.

I had worked at the company for two years before I was promoted to a managerial position.

In storytelling

She had just stepped onto the stage when suddenly, the lights went out!

My wife and I had always wanted to visit Australia, so when we retired, we booked a trip.

Ava: How was your weekend away?

Liam: It was great! But we had a bit of a scare on the way there.

Ava: Oh no, what happened?

Liam: Well, we’d already left the city when I realized I had forgotten my wallet.

Ava: Seriously?

Liam: Yeah, but luckily Emma had brought some cash, and I’d booked the hotel online the night before. So we were okay.

News report

The country had undergone years of political unrest before the revolution.

Past perfect vs. simple past

When talking about two past actions, use the past perfect for the earlier event and the past simple for the later one. Here’s an example:

- By the time she arrived at the airport, her flight had already taken off.

By the time is a very common phrase in the past perfect tense.

Now, compare these sentences. Which shows that the children finished their homework before I got home?

- When I got home, my children finished their homework.

- When I got home, my children had finished their homework.

The children finished before I got home in the second one. In the first, I got home and then they finished their homework.

When NOT to use the past perfect tense

We don’t tend to use the past perfect tense when the order of events is clear from the context. In that case, we usually use the past simple. For example:

- First, we went to the cinema and then we had dinner.

- He said goodbye to everyone before he left.

The order of events is very clear from the words first, then and before, so it’s not necessary to use the past perfect.

The role of “just” and other modifiers

In the past perfect tense, modifiers like just, already, never, and yet help to clarify timing, emphasis, and nuance in relation to a past event.

- Just emphasizes that something happened a very short time before another past action.

Ex. She had just left the office when the phone rang.

- Already highlights that something was completed earlier than expected.

Ex. He’d already finished dinner when I arrived.

- Never adds a sense of surprise or emphasis about something that hadn’t happened at any time before a specific past moment.

Ex. I’d never seen snow before my trip to Canada.

- Yet is used in negative sentences and questions to ask or state whether something had happened up to that point.

Ex. When we left the house, the mail hadn’t arrived yet.

Common mistakes learners make with the past perfect

- Forgetting had

Learners sometimes forget to add had in the past perfect tense.

- I been to the UK before. ❌

This structure, without had, is common in some English dialects, but it’s not standard. Don’t misplace had when using the past perfect!

- Overusing the past perfect

We explained above that it’s more appropriate to use the past simple tense when the order of events is clear. We also don’t use the past perfect when we have a chain of unrelated events.

We usually use the past simple for this:

- I woke up, ate breakfast, and went to work.

Having a native-level teacher is key when you’re trying to learn how and when to use the past perfect (and any other tenses) accurately. If you’re trying to learn English, Lingoda’s native speaking teachers not only know instinctively which tense should be used, but they can also explain why and provide plenty of examples.

Learn English with Lingoda

How it works

Past perfect vs. pluperfect: Is there a difference?

In English, the tenses referred to as the past perfect and the pluperfect are the same. Modern textbooks and courses tend to use the term past perfect. The same is true in other languages: the past perfect in German (Plusquamperfekt) might also be referred to as the pluperfect in English.

What is an example of past perfect vs past simple?

When I got home, my children had already eaten all the cake. (They ate it before I got there.)

When I got home, my children and I ate the cake. (We ate it together after I arrived home.)

What are the keywords for the past perfect?

A sentence containing had + -ed verb is in the past perfect. By the time is often a key indicator of this tense.

Past perfect tense, future fluent you

The past perfect tense helps you express the order and duration of past events, and it adds clarity to storytelling, professional communication, and academic writing. You now know how to form it, when to use it, and just as importantly, when not to.

If you want to take your grammar and fluency to the next level, Lingoda offers small group classes with native-level teachers who provide expert feedback and real-life examples. Learn to speak from day one, build confidence through practice, and enjoy flexible scheduling to suit your lifestyle. Start using advanced grammar like the past perfect naturally and accurately. Your future fluent self will thank you.

A practical guide to German irregular verbs

The term irregular applies to all German verbs that don’t follow standard conjugation rules. But within this broad category, there are important distinctions.

Strong verbs have stems that change vowels in certain tenses — for example, fahren (to go) becomes fuhr (Präteritum/past tense) and gefahren (Perfekt/past participle). In contrast, truly irregular verbs, like sein and haben, aren’t consistent and often change both their stems and endings in unexpected ways.

The good news? German has fewer irregular verbs than English. With some guidance and a bit of practice, you’ll find these patterns easier to grasp than you might think.

- How irregular verbs behave in German grammar

- The 5 main patterns of German strong verbs

- Present-tense conjugation table for common irregular verbs

- Tips to learn German irregular verbs faster

- German irregular verbs for English speakers: What’s easier (and harder)?

- FAQ

How irregular verbs behave in German grammar

Many irregular verbs still stick to the general structure of verb stem + conjugated ending, though they may differ from regular verbs in how the stem changes. This irregularity typically pops up in the du and er/sie/es forms, where the stem undergoes a vowel shift known as Ablaut. For example:

- nehmen (to take) → du nimmst, er/sie/es nimmt

- sehen (to see) → du siehst, er/sie/es sieht

Some verbs go beyond the Ablaut and show irregularities not only in the stem, but also in their endings. Such verbs are considered truly irregular and they include essential ones such as:

- haben (to have) → ich habe, du hast, er/sie/es hat

- sein (to be) → ich bin, du bist, er/sie/es ist

- werden (to become) → ich werde, du wirst, er/sie/es wird

Frustrated yet? It’s worth noting that the irregularities in German verbs aren’t simply random. They have historical roots that go back to earlier stages in the development of Germanic languages. The vowel changes we see (and struggle with) today are the result of systematic sound shifts that occurred centuries ago. Knowing this background isn’t strictly necessary, but it can help you see irregular verbs as part of a deeper structure rather than as agents of chaos.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

The 5 main patterns of German strong verbs

As you’ve probably noticed, most so-called “irregular” verbs are actually strong verbs that follow recognizable patterns. The Ablaut occurs here in a systematic and predictable way — mainly in the second-person singular (du) and third-person singular (er/sie/es) forms of the present tense, as well as in the past tense and participles. While you’ll still need to memorize these verbs individually, understanding how and where these irregularities occur will help you recognize patterns and conjugate verbs in German more easily.

All in all, there are five main patterns of German strong verbs, each defined by a specific sequence of vowel changes across tenses.

Ablaut pattern: e → i

In these verbs, the stem changes from e to i in the second- and third-person singular:

- geben (to give) → du gibst, er/sie/es gibt

- essen (to eat) → du isst, er/sie/es isst

- vergessen (to forget) → du vergisst, er/sie/es vergisst

Ablaut pattern: e → ie

The stem vowel e of these verbs becomes ie in singular forms:

- lesen (to read) → du liest, er/sie/es liest

- sehen (to see) → du siehst, er/sie/es sieht

- empfehlen (to recommend) → du empfiehlst, er/sie/es empfiehlt

Ablaut pattern: a → ä

Here, a takes an umlaut and becomes ä:

- fahren (to drive) → du fährst, er/sie/es fährt

- schlafen (to sleep) → du schläfst, er/sie/es schläft

- tragen (to carry, to wear) → du trägst, er/sie/es trägt

Past-tense Ablaut pattern: i → a (or i → a → u)

These changes occur primarily in the simple past and past participle:

- sitzen (to sit) → ich saß, du saßt, er/sie/es saß

- liegen (to lie) → ich lag, du lagst, er/sie/es lag

- finden (to find) → ich fand, du fandest, er/sie/es fand

Some of the verbs in this group follow a full three-step pattern, e.g., beginnen (to begin) → begann → begonnen.

Irregular / mixed verbs (unpredictable forms)

These verbs don’t fit neatly into any Ablaut pattern and must be memorized:

- bringen (to bring) → ich bringe, du bringst, er/sie/es bringt

- wissen (to know) → ich weiß, du weißt, er/sie/es weiß

- tun (to do) → ich tue, du tust, er/sie/es tut

- senden (to send) → ich sende, du sendest, er/sie/es sendet

What our students of German say

Present-tense conjugation table for common irregular verbs

The following table contains a list of German irregular verbs conjugated in the present tense, with the Ablaut in bold if present. These verbs are incredibly important to know, since you’ll encounter them often in daily interactions.

| Verb | ich | du | er/sie/es | wir | ihr | sie/Sie |

| beginnen (to begin) | beginne | beginnst | beginnt | beginnen | beginnt | beginnen |

| bitten (to ask) | bitte | bittest | bittet | bitten | bittet | bitten |

| empfehlen (to recommend) | empfehle | empfiehlst | empfiehlt | empfehlen | empfehlt | empfehlen |

| essen (to eat) | esse | isst | isst | essen | esst | essen |

| fahren (to drive) | fahre | fährst | fährt | fahren | fahrt | fahren |

| finden (to find) | finde | findest | findet | finden | findet | finden |

| geben (to give) | gebe | gibst | gibt | geben | gebt | geben |

| gehen (to go) | gehe | gehst | geht | gehen | geht | gehen |

| haben (to have) | habe | hast | hat | haben | habt | haben |

| halten (to hold) | halte | hältst | hält | halten | haltet | halten |

| kennen (to know, e.g., a person) | kenne | kennst | kennt | kennen | kennt | kennen |

| laufen (to run) | laufe | läufst | läuft | laufen | lauft | laufen |

| lesen (to read) | lese | liest | liest | lesen | lest | lesen |

| nehmen (to take) | nehme | nimmst | nimmt | nehmen | nehmt | nehmen |

| raten (to guess) | rate | rätst | rät | raten | ratet | raten |

| rufen (to call) | rufe | rufst | ruft | rufen | ruft | rufen |

| sehen (to see) | sehe | siehst | sieht | sehen | seht | sehen |

| sein (to be) | bin | bist | ist | sind | seid | sind |

| trinken (to drink) | trinke | trinkst | trinkt | trinken | trinkt | trinken |

| tun (to do) | tue | tust | tut | tun | tut | tun |

| vergessen (to forget) | vergesse | vergisst | vergisst | vergessen | vergesst | vergessen |

| verlassen (to leave) | verlasse | verlässt | verlässt | verlassen | verlasst | verlassen |

| wachsen (to grow) | wachse | wächst | wächst | wachsen | wachst | wachsen |

| werden (to become) | werde | wirst | wird | werden | werdet | werden |

| ziehen (to pull, to move) | ziehe | ziehst | zieht | ziehen | zieht | ziehen |

| zwingen (to force) | zwinge | zwingst | zwingt | zwingen | zwingt | zwingen |

Tips to learn German irregular verbs faster

Learning German irregular verbs can be easier than expected if you know the right strategies.

We’ve already covered the first and most important one: recognizing common stems and endings. Most irregular verbs use the standard endings in the present tense. But a small group of highly irregular verbs — like sein, haben and werden — have different or shortened endings that you’ll need to memorize separately. Once you’ve set those aside, you can focus on the stems of the remaining strong verbs and start learning the five main Ablaut patterns.

Another helpful tip concerns so-called “mixed” verbs. These verbs can be tricky because they look like regular verbs in the present tense, but their stems are irregular in the simple past and past participle. It’s best to learn them as a group, focusing on their past forms and using tools like flashcards or tables, such as the one below:

| Verb | Simple past | Participle |

| denken (to think) | dachte | gedacht |

| bringen (to bring) | brachte | gebracht |

| kennen (to know, e.g., a person) | kannte | gekannt |

| nennen (to name, to call) | nannte | genannt |

| rennen (to run) | rannte | gerannt |

Regardless of which kind of irregular verb you’re dealing with, a fun and effective way to learn them is by listening to and singing along with songs, such as those by Lern DEUTSCH durch SONGS. Apps and online tools such as the German Verb Conjugator can also help you practice basic German verbs and conjugation.

Of course, nothing beats practicing with native-level teachers, like those from Lingoda. Already in our German A1 course, you’ll start learning the most common irregular verbs.

German irregular verbs for English speakers: What’s easier (and harder)?

English and German are both Germanic languages, so they share similarities in verbs and verb behavior. If a verb is strong in English, it tends to be strong in German, too. In many cases, even the vowel changes adhere to comparable patterns. For example:

| English | German |

| sing, sang, sung | singen, sang, gesungen |

| drink, drank, drunk | trinken, trank, getrunken |

| begin, began, begun | beginnen, begann, begonnen |

German actually has fewer irregular verbs than English — around 200, compared to nearly 300 in English. And most German irregular verbs conform to clear, consistent patterns. In contrast, many English irregular verbs have completely unpredictable past forms that you simply have to memorize.

Naturally, German has its challenges, too. Pronunciation and spelling changes can be a bit confusing at first, especially when strong verbs change their vowel in the present tense (e.g., fahren → fährst). Plus, there are more verb forms to learn; German draws a clearer distinction between the simple past (ich ging) and the perfect tense (ich bin gegangen) than English does.

In short, German irregular verbs are far more regular than they seem. With time, practice and a bit of pattern-spotting, they can actually become one of the more manageable parts of your learning journey.

How many irregular verbs are in German?

German has around 200 irregular verbs. That’s fewer than in many other languages, like English (which has nearly 300!).

How do you know if a verb is irregular in German?

Irregular verbs typically do not follow the regular conjugation patterns of weak verbs, which only add simple endings. They often undergo a vowel change in their stem, called Ablaut, in their present and past forms.

Mastering irregular German verbs

German irregular verbs tend to pop up quite often, so you’ll run into them early in your journey to mastering the language. Are you introducing yourself? Then you’re probably already using the irregular verb sein. Telling your doctor you have a fever? That means you’re using haben, another essential irregular verb.

Learning these verbs can seem confusing, but they’re generally easier to handle than their English counterparts. There are fewer of them, and most follow clear and predictable patterns.

If you’re looking for a supportive partner to help you learn German, Lingoda is here for you. With certified native-level teachers and flexible class schedules, our German courses give you ample opportunities to practice irregular verbs in real conversations at your own level and pace.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

How to introduce yourself in German: A step-by-step guide for beginners

Introducing yourself in German is easier than you might think! Whether you’re greeting someone formally, sharing your name with a new acquaintance, or talking about where you’re from, a few key expressions can help you ace your first impression.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through the essentials — with practical tips and pronunciation help. Let’s get started!

- Begin with a greeting

- Say your name

- Where are you from?

- How to say your age in German

- Talk about where you live

- Mention your job or studies

- Share hobbies or interests

- Ending the introduction politely

- Bonus – Introducing yourself over the phone

- What NOT to do when introducing yourself

- FAQs

Begin with a greeting

The first step to introducing yourself is getting the greeting right. And there are a number of ways to greet someone in German, depending on the context, time of day and level of formality.

Formal and informal greetings

German has formal and informal ways to say hello. “Hallo!” is the most widely used informal greeting, and it’s easy for English speakers to remember. If you want to sound a bit more polite, you can try “Guten Tag” (Good day). In southern Germany and Austria, you might also hear “Grüß Gott,” which literally translates to “God bless.”

Examples and pronunciation tips

Here are some common German greetings along with their pronunciation:

| German | Pronunciation | English |

| Guten Tag | goo-ten tahk | good day |

| Hallo | hah-loh | hello |

| Grüß Gott | groos got | God bless (regional greeting, only used in Southern Germany and Austria) |

| Guten Morgen | goo-ten mor-gen | good morning |

| Guten Abend | goo-ten ah-bent | good evening |

Tip: German pronunciation is clear and distinct. The “r” in Morgen is either softly rolled or pronounced in the back of the throat, depending on the region, while the “ü” in Grüß Gott requires the same round lips you’d use when forming a whistle.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Say your name

‘Ich heiße…’ vs. ‘Mein Name ist…’

When introducing yourself in German, you have two options. “Ich heiße…“ (I am called…) is the most widely used, while “Mein Name ist…“ (My name is…) is reserved for business or official contexts.

How to ask for someone else’s name

To ask for someone’s name in an informal situation, use “Wie heißt du?“ (What’s your name?). When you need to sound more polite, use “Wie heißen Sie?“.

The key difference between these forms lies in the du (informal) and the Sie (formal), both of which can be used as a second-person pronoun (“you” in English). Germans take these distinctions seriously, so using the correct form helps set the right tone.

Where are you from?

‘Ich komme aus…’ and alternatives

The most common way to state where you’re from is “Ich komme aus…“ (I come from…). You might also hear “Ich bin aus…” (I am from…), which is slightly more informal.

When mentioning countries and cities, remember that German capitalizes all nouns. For example:

- Ich komme aus Deutschland. (I come from Germany.)

- Ich komme aus der Hauptstadt Berlin. (I am from the capital, Berlin.)

Asking where someone else is from

To ask someone where they’re from in an informal setting, use “Woher kommst du?” (Where do you come from?). If you need to speak formally, use “Woher kommen Sie?” instead.

How to say your age in German

Using ‘Ich bin … Jahre alt’

When stating your age in German, the standard phrase is “Ich bin … Jahre alt“ (I am … years old). You can also simply say “Ich bin 35” — it’s still perfectly clear.

To ask someone’s age, you can say “Wie alt bist du?“ (How old are you?) in informal situations or “Wie alt sind Sie?“ when speaking formally.

Cultural note: Age and formality in Germany

Although asking about someone’s age is generally acceptable among children, teenagers and young adults, it may be considered impolite when speaking with older individuals or in professional environments, where people usually don’t discuss age unless it’s relevant. If you’re unsure whether to ask, it’s best to wait until the topic comes up naturally.

What our students of German say

Talking about where you live

To say where you live in Germany, the most common phrase is “Ich wohne in…“ (I live in…). This works for neighborhoods, cities and countries alike. For example:

- Ich wohne in Köln. (I live in Cologne).

If you want to be more specific and mention your street, you can say “Ich wohne in der …straße.“ (I live on … street). For example:

- Ich wohne in der Goethestraße. (I live on Goethe Street).

To talk about a district or area within a city, you can say “Ich wohne im Stadtteil …“ (I live in the … district). For example:

- Ich wohne im Stadtteil Kreuzberg. (I live in the Kreuzberg district.)

Mention your job or studies

To inquire about what someone does professionally, you can ask “Was bist du von Beruf?” (What’s your profession?) in informal situations or “Was machen Sie beruflich?” in formal ones.

Some common professions in German are:

- Der Arzt, die Ärztin (doctor)

- Der Lehrer, die Lehrerin (teacher)

- Der Ingenieur, die Ingenieurin (engineer)

- Der Künstler, die Künstlerin (artist)

- Der Mechaniker, die Mechanikerin (mechanic)

- Der Bäcker, die Bäckerin (baker)

Share hobbies or interests

To talk about your hobbies in German, you can use “Ich interessiere mich für…“ (I am interested in…) followed by a noun, or simply “Ich [verb] gern…“ (I like to…).

- Ich interessiere mich für Musik. (I am interested in music.)

- Ich spiele gern Fußball. (I like to play soccer.)

Notice how gern (gladly, like to) goes after the verb in this construction:

- Ich lese gern. (I like to read.)

- Ich lese gern Gedichte. (I like to read poetry.)

Ending the introduction politely

To wrap up an introduction, you can say “Schön, dich/Sie kennenzulernen“ (Nice to meet you) using one or the other pronoun depending on the formality. Alternatively, “Es freut mich“ (I’m pleased) is a shorter, cordial way to express the same sentiment.

A polite handshake is common in formal settings, while a warm smile generally suffices in casual encounters. Germans value sincerity above expression, so body language tends to be more reserved.

Bonus: Introducing yourself over the phone

Why phone conversations feel tougher

Introducing yourself over the phone in German can feel more challenging than in person because you don’t have facial expressions or body language to rely on. Germans also tend to speak directly and efficiently on the phone, making it essential to start with a clear introduction.

Phrases to use on the phone

- Hallo, hier ist… (Hello, this is …)

- Guten Tag, mein Name ist … (Good day, my name is…)

- Könnte ich bitte mit … sprechen? (Could I speak with … please?)

- Worum geht es? (What is this about?)

- Könnten Sie das bitte wiederholen? (Could you repeat that, please?)

What not to do when introducing yourself

While being formal in casual settings might sound overly stiff, being too informal in professional settings can come across as something far worse: disrespectful. Err on the side of caution and formality to avoid awkward encounters.

Also, try to keep your introduction simple and natural, and be mindful of personal space — Germans appreciate a respectful distance, and overly enthusiastic gestures might feel intrusive.

How do I say ‘My name is…’ in German?

You can say “Ich heiße…“ (I am called…) or “Mein Name ist…” (My name is…). The first is more conversational, while the second is more formal.

Take the leap: Introduce yourself in German

Introducing yourself in German is simple once you know the key phrases. Sharing where you’re from, your age, where you live and your hobbies can help you open the door to meaningful connections with locals!

Want to practice real-life German with native speakers? Lingoda’s small group classes offer interactive learning environments to help you gain confidence in everyday conversations. Try one out and start speaking naturally!

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

The top 5 resources for easy German news

Looking for a simple way to boost your German? Easy German news articles are a fantastic tool. For beginner and intermediate learners, diving into complex German newspapers might feel overwhelming. Luckily, many platforms offer simplified articles and audio stories specifically designed for learners. Here, we’ve rounded up the top 5 resources for easy German news to help you stay informed and improve your language skills at the same time.

- Why incorporate German news into your learning routine?

- Top platforms offering simplified news in German

- Tips for maximizing learning with easy German news

- FAQs

Why incorporate German news into your learning routine?

There are so many reasons to read or listen to the news in a language you’re learning! Easy news in German gives you access to authentic written and spoken materials in a learner-friendly format. You can learn contemporary language while helping you pick up idiomatic expressions and vocabulary used by native speakers. You can also choose stories that interest you to make the learning process more engaging.

Many of the resources we highlight offer visual and audio versions of stories, too. This allows you to tailor your practice to your learning style (whether you learn better by reading or listening) and gives you a chance to work on weaker skills by combining both. You might also want to explore the best podcasts to learn German, many of which offer transcripts alongside the audio.

To make the most of easy German news resources, try to stay active while learning. Engage with the content to make sure you remember new vocabulary and structures: write a summary of the article or create example sentences with the new vocabulary. If you can, discuss the articles with other German learners and try to use some of the new language — this is great if you attend German classes. And to improve your pronunciation, repeat after the speaker or shadow them (speak at the same time as them).

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Top 5 platforms offering simplified news in German

1. Nachrichtenleicht

For beginners, Nachrichtenleicht is an excellent news platform with simplified articles covering current events. After each article, certain key words are explained in simple German (there are no translations), allowing you to further expand your vocabulary. You can also listen along to audio versions of the stories as you read.

2. News in Slow German

Designed for beginner and intermediate learners, News in Slow German features news stories delivered at a deliberately slower pace. You can choose to speed up the audio when you gain confidence or even slow it down further if necessary. Transcripts are provided, along with explanations of certain terms. Please note that to access most of the content on News in Slow German, you’ll need a paid subscription.

3. Deutsche Welle’s ‘Langsam Gesprochene Nachrichten’

For those at a B2-level who still need support to understand authentic listening materials, Deutsche Welle’s ‘Langsam Gesprochene Nachrichten‘ is ideal. With new uploads daily from Monday to Saturday, you can keep up with the latest stories in an easy-to-digest format. The audio is read slowly, and full transcripts are provided if you’d like to read along.

4. Sloeful’s simple German news

Sloeful offers simplified German news suitable for A2 to B1-level learners. The articles focus on real past events, which are told through a simpler lens to help German learners follow along. From floods in Münster to lottery winners flying to the Moon, there’s a range of vocabulary-rich topics to discover.

5. Todaii Easy German

For a broad sweep of stories, try Todaii Easy German. Articles from a range of official sites, including DW and Tagesschau, are uploaded daily. Learners can filter by level (from A0 to C2), news source, and topic, from travel to politics to science.

What our students of German say

Tips for maximizing learning with easy German news

To make sure you don’t get overwhelmed:

- Choose beginner-friendly sources with level-appropriate vocabulary. Record new words in a notebook or app and review them regularly. Writing personalized examples is a great way to make sure new vocabulary sticks.

- Start with slow-spoken news before working up to more rapidly spoken stories. Many of the sites above offer slower audio, so try listening to stories a few times, increasing the speed as your understanding improves. Transcripts are very helpful at first too, particularly if the story contains a lot of new vocabulary or the speaker has an unfamiliar accent.

- Investigate unfamiliar cultural references. They’re a chance to learn even more! You may want to use a search engine, read a similar article in your own language, or take any questions you have to your language tutor if possible. Native-speaking tutors can share a wealth of cultural information.

- Finally, while reading or listening to the news is an excellent way to immerse yourself in German, it doesn’t provide you with a structured path forward in the way a German course can. Lingoda’s CEFR-aligned courses help you learn German systematically and are the perfect complement to independent reading and listening practice with easy German news.

Are there German news platforms specifically designed for beginners?

Yes! Nachrichtenleicht and News in Slow German have easy German news for beginners.

Can listening to slow-spoken German news help with comprehension?

Absolutely. Listening to slower audio can help comprehension. You can then speed up the audio as you gain confidence.

How often should I read German news to see improvement?

Aim to read at least one article per day and explore a variety of topics to broaden your vocabulary and deepen your cultural knowledge.

The benefits of easy German news for beginners

Reading easy German news articles is a powerful step in your journey toward fluency. You’ll discover topics that interest you and learn the vocabulary to talk about them confidently. But, though news articles provide useful practice materials, they don’t offer a clear path for progression.

The best way to learn German is to use a combination of authentic materials and a structured course. Lingoda’s small-group classes focus on teaching real-life language, just like you can learn from news articles, but have the additional benefit of allowing you to use all of the rich vocabulary you’re learning. The native-level teachers can add rich cultural context, and you can discuss what you’ve learned with like-minded classmates.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Why Germans Often Reply in English—And What It Means for Language Learners

Let’s imagine you’re in a cafe in Berlin. You order a coffee and a pastry in perfect German. The cashier replies in English. You ask where the bathroom is, again in perfect German. Once again, the cashier replies in English. You end the exchange with a frustrated, “Danke… (for not helping me practice my German).”

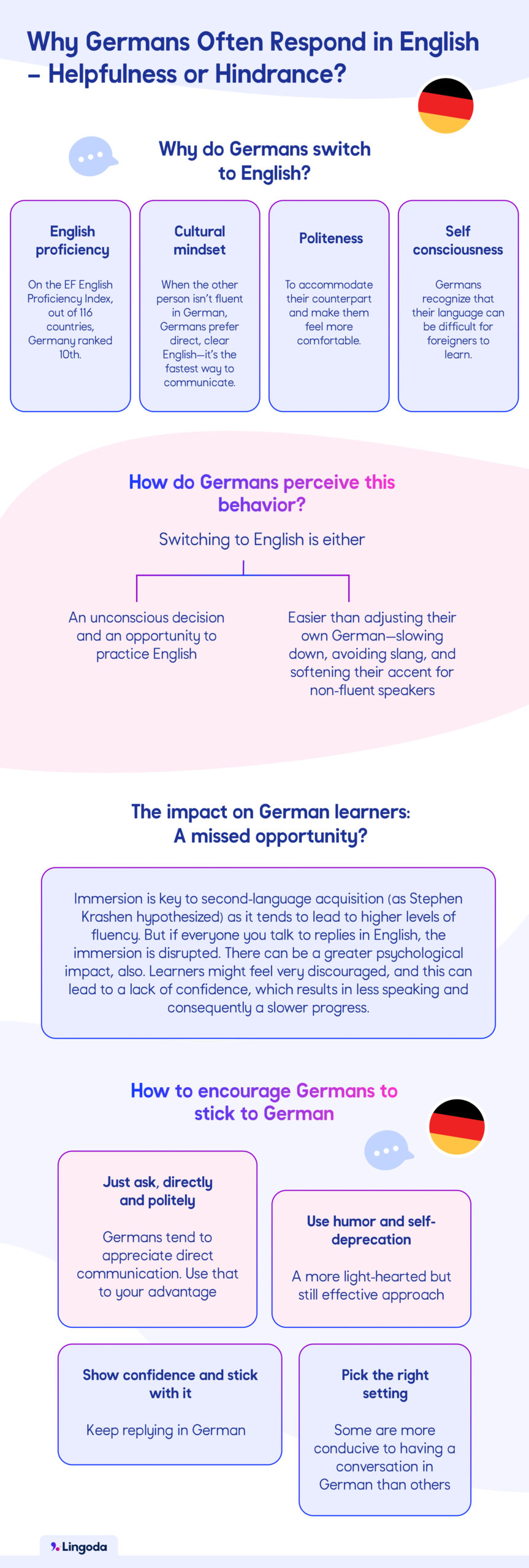

So, why do so many German people switch to English when a foreigner speaks their language? Is it helpful or a hindrance to language learners? And can you stop them? In this article, we’re going to answer all of these questions.

- Why do Germans switch to English?

- How do Germans perceive this behavior?

- The impact on German learners: A missed opportunity?

- How to encourage Germans to stick to German

Why do Germans switch to English?

High English proficiency in Germany

One reason Germans often switch to English is simply that they speak it more fluently than you speak German, particularly if you’ve just started learning. English proficiency in Germany is rated “high” on the EF English Proficiency Index. In fact, out of 116 countries, Germany ranked tenth. Most Germans start learning English in elementary school and so they have a considerable head start on people who begin their journey with German later in life.

Cultural mindset: Efficiency and directness

Germans tend to communicate directly—what they say is what they mean. In many situations, conversations are functional and to the point. On the other hand, people trying to practice their language skills often pause, hesitate, and wrestle with words. Many Germans see switching to English as the quickest way to communicate, and in a culture that values efficiency, faster often means better. As one user writes in Reddit’s ‘Ask A German‘ forum, “I will immediately switch to english the second I realise the conversation will become inefficient otherwise.”

A matter of politeness?

The tendency to switch to English also comes from politeness and empathy. As Reddit user muesham puts it in the r/German forum, “If the other person seems to be nervous about speaking German, then we automatically feel like we should accommodate them by switching to a language that would make them feel less nervous.”

Stereotypes about foreigners and language abilities

Many German people also recognize that their language can be difficult for foreigners to learn. From the case system to the intimidatingly long words, German poses multiple challenges. Wanting to ease the burden for foreigners, Germans sometimes switch to English.

How do Germans perceive this behavior?

Often, Germans switch to English without even realizing it.Reddit user muesham continues, “[Switching to English is] not a conscious decision, it’s just what we’re automatically inclined to do.” Other Germans simply like speaking English and take any opportunity to do so, as a user writes in the ‘Ask a German’ forum.

There’s also a practical side, as user MrsButtercheese says in the same Reddit forum: “It can be kinda difficult to speak German with someone who isn’t also native or at least properly fluent, because you have to… [d]ial back your own accent, avoid slang and local dialect, slow down, etc.”

So, if you find yourself frustrated because a German speaker keeps switching to English, remember they might not realize they’re doing it. They could just be trying to help—or practicing their English, too.

The impact on German learners: A missed opportunity?

Constantly switching to English can affect German learners in several ways. Studies consistently show that immersion is one of the most effective ways to learn a new language. If you’re in Germany, being immersed in the language should be easy. But if everyone you talk to replies in English, your immersion is disrupted, which harms your ability to pick up the language.

It can also be frustrating for learners who find themselves in a constant battle to get someone to reply in German. Many end up feeling stuck in a loop: they try to speak German, get a reply in English, and start questioning their skills. Ultimately, this lack of confidence will result in less speaking and slower progress.

Stephen Krashen’s input hypothesis

When people switch to English, German learners are not only missing out on an opportunity to speak but on an opportunity to listen, too. Linguist Stephen Krashen, in his Input Hypothesis, states: “We acquire language in one way and only one way: when we are exposed to comprehensible input that is slightly beyond our current level.” So, having the chance to listen to and try to understand native German speakers is vital for learners who want to make progress in the language.

How to encourage Germans to stick to German

Just ask, directly and politely

We already covered how German people favor a direct communication style, so use that to your advantage and ask them outright to speak German. Say this:

- Ich möchte mein Deutsch verbessern, könnten wir bitte Deutsch sprechen? (I would like to improve my German. Could we please speak German?)

Take the advice of Scott Thornbury, author of How to Teach Speaking, when he says: “Language learning is about negotiation. If the conversation defaults to English, it’s the learner’s task to renegotiate the rules and steer it back to the target language — again and again.”

Use humor and self-deprecation

You can also take a more light-hearted approach when asking a German person to stick to German. Try these:

- “Mein Deutsch ist noch nicht so gut, aber deins ist perfekt. Könntest du mir beim Üben helfen?” (My German isn’t very good, but yours is perfect! Can you help me practice?)

- “Dein Englisch ist schon so gut! Wäre es okay, wenn wir an meinem Deutsch arbeiten?” (Your English is already so good! Do you mind if we work on my German?)

If that fails, make yourself a badge that says “Nur Deutsch, bitte!” (German only, please!) and point to it when necessary.

Show confidence and stick with it

If you don’t feel comfortable asking directly (or the person ignores your pleas), be persistent and keep replying to them in German. Don’t worry about why they’re replying in English; just keep your confidence up and plow on.

Pick the right setting

Certain settings are better suited to having a conversation in German than others, and there are times when you may have to accept a reply in English. As Reddit user ExecWarlock writes, “If you are in a store, business environment or other similar situations, people are not your language teacher… it can be annoying and/or time-consuming for them to try to understand broken German.” However, if you get chatting with someone in a more relaxed, less transactional situation, it should be perfectly fine to ask your conversation partner to stick to German.

Striking a balance

For English speakers who arrive in Germany eager to practice their budding German, it can be frustrating and discouraging when the locals reply in fluent English. It’s crucial to remember that this is mostly well-intentioned, whether the German person wants to save you some trouble, ensure more efficient communication, or just practice their own English.

German learners need to become comfortable expressing their desire to practice while taking into consideration where and when they’re doing it. And Germans, too, can be mindful that constant switching might unintentionally discourage learners and slow down their learning progress. Ultimately, mutual understanding (and maybe a “Nur Deutsch, bitte” badge) leads to better language exchange experiences.

Begin your personal language journey

- Courses tailored to your learning needs

- Qualified native-level teachers

- Expert-designed curriculum

- Live classes with small group sizes

Essential Spanish food terms for every situation

Spanish-speaking countries are known for having some of the most amazing flavors around the world. You’re probably already highly motivated to learn at least some basic Spanish food vocab.

From being able to buy groceries and order food in Spanish to becoming familiar with local eating habits, you’ll quickly see that getting food words in Spanish down will open up a new (and delicious) world to you. So, let’s feed that appetite and take a look at this comprehensive food glossary!

- Core Spanish food vocabulary

- Beverages in Spanish

- Sweet treats and desserts

- Dishes and meals in Spanish

- Flavors and cooking terms in Spanish

- Understanding Spanish mealtimes and food culture

- FAQs

Core Spanish food vocabulary

As an appetizer, we’ll start with essential Spanish food vocab. These are Spanish words you need to know to go shopping, order food at Spanish-speaking restaurants and even talk about dietary restrictions or allergies.

Let’s dive into how to say the most common vegetables, proteins and fruits in Spanish:

Vegetables (verduras / vegetales)

| Spanish | English |

| aguacate | avocado |

| alcachofa | artichoke |

| apio | celery |

| berenjena | eggplant |

| brócoli | broccoli |

| cebolla | onion |

| cilantro | cilantro |

| champiñón | mushroom |

| col/repollo | cabbage |

| elote (Mexico)choclo (Central & South America)maíz (Spain) | corn |

| espárragos | asparagus |

| espinacas | spinach |

| jitomate (Mexico)tomate (general) | tomato |

| lechuga | lettuce |

| papa (Latin America)patata (Spain) | potato |

| pepino | cucumber |

| pimiento | pepper |

| rábano | radish |

| zanahoria | carrot |

Here are example sentences using these words:

- Soy alérgico/a a la cebolla (I’m allergic to onion).

- Me encanta la lasaña de berenjena (I love eggplant lasagna).

- En México comen mucho rábano (They eat a lot of radish in Mexico).

- No me gustan las espinacas (I don’t like spinach).

Fruits (frutas)

| Spanish | English |

| cereza | cherry |

| ciruela | plum |

| durazno | peach |

| frambuesa | raspberry |

| fresa | strawberry |

| guayaba | guava |

| higo | fig |

| lima | lime |

| limón | lemon |

| mango | mango |

| manzana | apple |

| melón | melon |

| mora azul | blueberry |

| naranja | orange |

| pera | pear |

| piña | pineapple |

| plátano | banana |

| sandía | watermelon |

| toronja | grapefruit |

| uva | grape |

| zarzamora | blackberry |

- Adriana hace un pay de manzana delicioso (Adriana makes a delicious apple pie).

- El jugo de naranja me hace daño (Orange juice doesn’t sit well with me).

- El vino está hecho de uvas (Wine is made of grapes).

Proteins (proteínas)

| Spanish | English |

| atún | tuna |

| carne | meat |

| carne de res | beef |

| cerdo | pork |

| chorizo | chorizo |

| cordero | lamb |

| jamón | ham |

| pavo | turkey |

| pescado | fish |

| pollo | chicken |

| salchicha | sausage |

| salmón | salmon |

| tocino | bacon |

- No como carne, soy vegetariana/o (I don’t eat meat, I’m a vegetarian).

- Me gustan los waffles con tocino (I like waffles with bacon).

- La salchicha alemana es la mejor (German sausage is the best).

Grains (granos), nuts (nueces) and staple foods

| Spanish | English |

| aceite | oil |

| aceituna | olive |

| almendra | almond |

| arroz | rice |

| azúcar | sugar |

| especias | spices |

| cacahuate (Mexico)maní (South America/Caribbean)cacahuete (Spain) | peanut |

| cátsup | ketchup |

| frijoles | beans |

| garbanzos | chickpeas |

| lentejas | lentils |

| masa | dough |

| mayonesa | mayo |

| mostaza | mustard |

| nuez | walnut |

| pan | bread |

| pasta | pasta |

| pimienta | pepper |

| piñón | pinenut |

| trigo | wheat |

| sal | salt |

| salsa de chile | hot sauce |

| semillas | seeds |

| vinagre | vinegar |

- Mi cerveza favorita es la de trigo (Wheat beer is my favorite).

- Ya no tenemos vinagre (We ran out of vinegar).

- Le hace falta pimienta a la pasta (The pasta is missing some pepper).

- La sopa de lentejas es mi favorita (Lentil soup is my favorite).

Dairy (lácteos)

| Spanish | English |

| crema | cream |

| huevo | egg |

| leche | milk |

| mantequilla | butter |

| queso | cheese |

| suero de leche | buttermilk |

| yogurt | yogurt |

- Desayuno yogurt con fruta (I have fruit with yogurt for breakfast).

- No me gusta el queso fuerte (I don’t like strong cheese).

Beverages in Spanish

How are we gonna wash down all those small-plate tapas? Let’s order some drinks (bebidas)!

Common drinks (bebidas)

| Spanish | English |

| agua mineral (Mexico)agua con gas | sparkling water |

| agua natural | still water |

| café | coffee |

| chocolate caliente | hot chocolate |

| jugo (Latin America)zumo (Spain) | juice |

| leche | milk |

| licuado (Mexico)batido (Spain) | smoothie |

| limonada | lemonade |

| malteada | milkshake |

| refresco / soda | soda |

| té | tea |

| té helado | iced tea |

- Para mí un agua mineral, por favor (Sparkling water for me, please).

- Siempre ceno un licuado de plátano (I always have a banana smoothie for dinner).

Alcoholic beverages (bebidas con alcohol)

| Spanish | English |

| alcohol | alcohol |

| botella | bottle |

| cerveza | beer |

| cerveza de barril | draft beer |

| champaña (LatAm)champán (Spain) | champagne |

| cóctel | cocktail |

| ginebra | gin |

| shot (general)chupito (Spain) | shot |

| sidra | cider |

| vino | wine |

| vodka | vodka |

| whiskey | whiskey |

- Me da, por favor, una cerveza de barril (Can I get a draft beer, please?).

- El alcohol me causa resaca (Alcohol gives me a hangover).

- La sidra es muy suave (Cider is very smooth).

Pro tip: If you want to work on your Spanish vocabulary, joining classes is a game-changer. At Lingoda, you’ll learn vocab in an immersive manner. You can focus on speaking from day one and practicing real-life conversation skills. Plus, you can set your schedule however works best for you and choose between small group or private Spanish lessons.

Sweet treats and desserts

We’re approaching the end of our meal. If you fancy something sweet, take a moment to learn these food words in Spanish for sweet treats and desserts:

Popular Spanish desserts (postres)

| Spanish | English |

| churros | churros |

| flan | flan |

| torrijas | French toast |

| leche frita | fried milk pudding |

| roscón de reyes | Kings’ day circle bread |

| arroz con leche | rice pudding |

| tarta de Santiago | Santiago almond-flour cake |

- ¿Tienen churros con chocolate? (Do you have churros with chocolate?).

- El roscón de reyes se come en enero (Kings’ day bread is eaten in January).

What our students of Spanish say

Common sweet ingredients and foods

| Spanish | English |

| azúcar | sugar |

| canela | cinnamon |

| chocolate | chocolate |

| crema chantilly | whipped cream |

| dulce | candy |

| fruta | fruit |

| galleta | cookie |

| gelatina | jelly |

| helado (general)nieve (Mexico) | ice cream |

| hot cakes (Mexico)panqueques | pancakes |

| jarabe | syrup |

| mantequilla de cacahuatemantequilla de maní | peanut butter |

| mermelada | marmalade |

| miel | honey |

| miel de maple | maple syrup |

| crema pastelera (LatAm)natilla (Spain) | custard |

| nata | cream/whipping cream |

| pan dulce | pastry |

| pasta de hojaldre | puff pastry |

| pastel | cake |

| pay de queso | cheesecake |

| tarta (Spain, South America)pay (Mexico) | pie |

| vainilla | vanilla |

- No puedo comer azúcar debido a mi salud (I can’t eat sugar due to my health).

- El chocolate es mi dulce favorito (Chocolate is my favorite candy).

- Prefiero la miel de maple a la de abeja (I prefer maple syrup to honey).

- Se me antoja un sándwich de crema de cacahuate (I feel like a peanut butter sandwich).

Dishes and meals in Spanish

Let’s take a look now at some staple dishes and meal items in Spanish:

| Spanish | English |

| copa | glass |

| ensalada | salad |

| entrada | appetizer |

| guarnición | side dish |

| hamburguesa | hamburger |

| pan tostado | toast |

| plato | dish / plate |

| plato fuerte | main dish |

| postre | dessert |

| sandwichtorta (Mexico) | sandwich |

| sopa | soup |

| vinagretaaderezo | vinaigrettedressing |

- Prefiero la ensalada a la hamburguesa (I prefer the salad to the burger).

- La sopa va antes del plato fuerte (Soup comes before the main dish).

- A la ensalada le falta aderezo (The salad lacks dressing).

Flavors and cooking terms in Spanish

Learning vocabulary for describing flavors and cooking techniques can come in handy in different situations. Want to show appreciation for a meal? Or go through that great Spanish cookbook you got during your last holiday? We’ve got you.

Describing tastes, textures and flavors

| Spanish | English |

| ácido | sour |

| agridulce | sweet and sour |

| aguado | soggy |

| ahumado | smoky |

| bueno | good |

| caliente | hot |

| con hielo | iced |

| cremoso | creamy |

| crujiente | crunchy |

| dulce | sweet |

| fresco | fresh |

| frío | cold |

| grasoso | greasy |

| húmedo | wet |

| jugoso | juicy |

| malo | bad |

| picantepicoso | hot |

| ricodelicioso | delicious |

| rostizado | roasted |

| salado | salty |

| seco | dry |

| suave | soft |

| tibio | warm |

This is how you can talk about flavor, temperature and texture:

- Está muy… picante / rico / salado / dulce (It’s very… spicy / delicious / salty / sweet).

- Está… caliente / frío (It’s… hot / cold).

- Es / Está … crujiente / suave / seco (It’s… crunchy / soft / dry).

Essential cooking verbs

| Spanish | English |

| agregar | add |

| asar | roast |

| poner | put |

| exprimir | squeeze |

| rallar | grate |

| amasar | knead |

| rebanar | slice |

| freír | fry |

| colar | strain |

| colocar | place |

| hervir | boil |

| hornear | bake |

| cortar | cut |

| lavar | wash |

| salpimentar | season |

| descongelar | defrost |

| limpiar | clean |

| marinar | marinate |

| medir | measure |

| mezclar | mix |

| tostar | toast |

| echar | pour |

| pelar | peel |

| pesar | weigh |

| servir | serve |

| untar | spread |

| enfriar | cool |

| picar | chop |

| voltear | flip |

Here are a few examples of how you might see these verbs in recipes:

- Voltea la carne para salpimentar y sírvela caliente (Flip the meat, season it and serve it hot).

- Pica la zanahoria y agrégala a la preparación (Chop the carrot and add it to the mixture).

- Hornea el pay por 45 minutos y sirve cuando aún esté tibio (Bake the pie for 45 minutes and serve it while still swarm).

- Lava el pollo, colócalo en un recipiente y déjalo marinar (Wash the chicken, place in a tray and let it marinate).

- Deja enfriar antes de servir (Let it cool before serving).

Measurements (medidas)

In Spain and Latin American countries, these are the most common measuring units used in cooking:

| Spanish | English |

| grados Celsius | Celsius degrees |

| kilogramo | kilogram |

| litro | liter |

| miligramo | milligram |

| mililitro | milliliter |

| onza | ounce |

| pizca | pinch |

- Horneamos el pastel a 200º por 30 minutos (We bake the cake at 200º for 30 minutes).

- Agregamos una onza de vodka (We add one ounce of vodka).

- Terminamos con una pizca de sal (We finish off with a pinch of salt).

Understanding Spanish mealtimes and food culture

Let’s check out some Spanish food vocab related to mealtimes and discuss some meal habits in Spain and Latin America:

Common Spanish meals and their names

| Spanish | English | Schedule |

| desayuno | breakfast | 7:00-9:00 |

| meriendasnack | snack | 11:00-11:30 and 17:00-18:00 |

| comidaalmuerzo | lunchlunchtime | 13:30 – 15:30 |

| cena | dinner | 21:00 – 22:30 |

| tapas | snacks | 13:30-15:00 or 20:30-22:30 |

- Para la cena habrá sopa de tomate (We’ll have tomato soup for dinner).

- El desayuno es la comida más importante del día (Breakfast is the most important meal of the day).

- Hablamos a la hora de la comida (Let’s talk at lunchtime).

Note: As you can see, dinner in Spain is served rather late compared to American dinner time. That’s why there’s snack time (merienda) in the afternoon. On the other hand, tapas are usually served with drinks –so they’re more like bar food.

Typical eating habits in Spain and Latin America

A common thread between Latin American countries and Spain is that lunch is the main meal of the day –this is when you’ll get the most substantial dish. Dinner, however, tends to be lighter.

One major difference is the role wine plays in Spanish food culture. It’s common, for instance, to find a bottle of wine at the lunch or dinner table. Having a glass or two is quite normal. In most Latin American countries, though, wine is mostly saved for the weekends. People don’t drink much alcohol during the working week unless there’s a celebration or a get-together with friends.

How mealtimes vary by region

Just like in Spain, many countries in Latin America –like Mexico and Argentina– also have three mealtimes (breakfast, lunch and dinner). However, in Mexico and Colombia, for example, dinner is served earlier, usually between 19:00 and 21:00. In Argentina, it’s typically between 20:00 and 23:00 (sometimes even later!).

A big difference, though, is that in Spain, kitchens are open only during mealtimes –so it’s not possible to have a meal just anytime you want. In Latin America, for its part, restaurants are usually open throughout the day or in the late afternoon.

What are the names of meals in Spanish?

| Spanish | English |

| desayuno | breakfast |

| meriendasnack | snack |

| comidaalmuerzo | lunchlunchtime |

| cena | dinner |

| tapas | snacks or small plates |

What is a typical Spanish food called?

Spain is home to some of the most mouthwatering food in the world (and fruity wine sangría, of course)! Typical dishes include: tortilla de patatas, jamón ibérico, churros, paella, gazpacho, pimientos padrón, pulpo a la gallega, croquetas and patatas bravas.

Feeling confident and hungry

Whether you’re thinking about moving or traveling to a Spanish-speaking country, learning the most common Spanish food terms –from cooking verbs to kitchen essentials– will help you navigate daily life like a pro. You’ll be able to shop (and chop!), order food at a restaurant and confidently express how much you liked your paella without a problem. And if you’re hungry for more vocabulary, join us at Lingoda today! Our fantastic teachers and focus on real-life conversations will give you the perfect boost.

Spanish transition words: What are they and how do we use them?

Spanish transition words are an essential part of Spanish grammar. Just like Spanish prepositions and other connecting words, these words help us establish logical links between different elements in a text, such as paragraphs, sentences and other syntactic groups.

Why is it important to learn them? Well, mastering the most common Spanish transition words will significantly boost your language skills. By using them, we develop a natural flow to our written and spoken communication. Whether we are looking to write a smooth work email or confidently engage in small talk in Spanish, these simple words help us guide our audience through our ideas with ease.

So, let’s dive into what transition words are and the purpose they serve. We’ll also take a look at some examples to get a better grasp on the topic. Let’s go!

- What are Spanish connecting words and transition words?

- Categories of Spanish transition words

- How to master Spanish transition words

- Bonus: Advanced transition phrases

What are Spanish connecting words and transition words?

Spanish connecting words are tools that create links between words, paragraphs and sentences. Transition words are a subtype of connecting words that act as bridges between ideas or arguments. They help the speaker transition from one sentence to the next in a coherent and natural way.

Transition words are crucial for cohesion. They facilitate comprehension. Without them, our texts and speech can come across as choppy or impersonal. This affects our ability to communicate effectively and engage our audience’s attention (even if our spelling and grammar are impeccable). In fact, they’re so essential that we can find equivalents in all languages, including English.

English vs. Spanish transition words

To illustrate what these connecting words are all about, let’s compare some Spanish and English transition words:

| English | Spanish |

| additionally | además |

| as a result | como resultado |

| as a consequence of | como consecuencia de |

| for example | por ejemplo |

| for this reason | por esta razón |

| furthermore | además |

| meanwhile | mientras tanto |

| nevertheless | sin embargo |

| soon | pronto |

| therefore | por lo tanto |

| to summarize | en resumen |

Now, imagine if we didn’t use transition words in English:

- With a transition word: I don’t think I’ll know anyone at the party. Nevertheless, I’ll still come (No creo que vaya a conocer a alguien en la fiesta. Sin embargo, sí iré).

- Without a transition word: I don’t think I’ll know anyone at the party. I’ll still come (No creo que vaya a conocer a alguien en la fiesta. Sí iré).

It feels disjointed without the transition word, right? The same is true in Spanish.

Categories of Spanish transition words

Spanish transition words allow us to contrast, expand and explain ideas. Let’s break them down into categories according to their use:

Transition words for time (chronology)

These let you connect ideas in relation to the time they occur. They’re particularly useful, for instance, when giving a chronicle, telling an anecdote or even writing a recipe.

Here are some common examples:

| Español | Inglés |

| al final | in the end |

| al mismo tiempo | at the same time |

| después | afterwards |

| entonces | then |

| finalmente | finally/lastly |

| inmediatamente | immediately |

| en resumen | in short |

| mientras/mientras tanto | meanwhile |

| primero/primeramente | first/firstly |

| pronto | soon |

| todavía | still |

| ya | already |

| luego | then/next/later |

This is how we can use some of them in a sentence:

- Primero, iremos al cine. Después, a cenar (First, we’ll go to the cinema. Then, to dinner).

- Lorena es estudiante de medicina; pronto será doctora (Lorena is a medical student; soon, she’ll be a doctor).

- Finalmente, agregamos la leche (Lastly, we add the milk).

What our students of Spanish say

Transition words for adding or expanding ideas

Looking to add context or introduce another detail? Check out these transition words:

| Spanish | English |

| además | furthermore, additionally, plus |

| asimismo | similarly |

| igualmente/de igual manera | likewise |

| por otro lado | on the other hand |

| también | also, as well |

| y | and |

- No sé si tengo ganas de salir esta noche. Además, mañana me levanto temprano (I’m not sure I feel like going out tonight. Plus, I’m getting up early tomorrow).

- Me lastimé el pie y me corté la mano (I hurt my foot and I cut my hand).

Transition words for explaining and giving examples

These words allow us to explain what we just said:

| Spanish | English |

| entre ellos/ellas | including |

| en otras palabras | in other words |

| es decir | that is to say, that is |

| por ejemplo | for example |

| ya que | since |

- Me gustan los deportes en el exterior. Por ejemplo, el tenis y el golf (I like outdoors sports. For example, tennis and golf).

- Los conectores nos ayudan a darle coherencia a la estructura de un enunciado. Es decir, a darle lógica (Connectors help us give coherence to a sentence structure. That is to say, to give it logic).

Note: These words come in particularly handy in academic contexts, since they are used to support our arguments. However, be careful not to overuse them or your content may become redundant.

Transition words for contrasting and comparing ideas

These help us compare ideas, objects or people:

| Spanish | English |

| aunque | although, while |

| a pesar de | despite |

| en cambio | on the other hand |

| como | like |

| por el contrario/otro lado | by contrast |

| pero | but |

| sino | but |

| sin embargo | however, nevertheless |

| no obstante | nevertheless |